The Straight Line Newsletter — Issue #15

In This Issue

- Dispute resolution wordings – Arbitration can be a good and useful tool, when used appropriately. Unfortunately, some client-authored contracts include clauses related to arbitration that sacrifice the architect’s best interests. John Hackett, Pro-Demnity’s VP Practice Risk Management explains how to recognize and avoid these unhealthy situations.

- Five things a Pro-Demnity lawyer does not want to hear – In this essay, John Little, a lawyer who regularly defends architects facing Claims, explains his five biggest bugbears, in the hope you won’t repeat them. If you’ve been in practice for any length of time, you’ve probably uttered at least one of these phrases. The main thing is to avoid the actions and circumstances that may have you sharing them with your lawyer when you face a Claim.

- Costs in Addition – Insurance terminology can be confusing. “Costs in Addition” (as with Pro-Demnity policies) means the costs incurred by the insurer to defend you are in addition to the limits available to pay damages – a good thing. The costs the insurer pays don’t erode the limits available to protect you. “Costs Included” (as with many other insurers’ policies) means the costs come out of the limits – a bad thing.

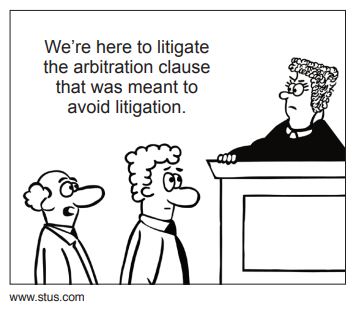

Dispute resolution wordings: Arbitration is a “four-letter word!”

Pro-Demnity has seen a marked increase in client-authored Dispute Resolution measures. Some of these provide for arbitration as an option, by “mutual consent,” in the event that negotiations or mediation fails. However, many of these measures do not include an option; instead, they require the parties to resort to “binding arbitration” to resolve disputes between the architect and the client, regardless of circumstances.

In other variants, the architect is obliged to participate as a party in an arbitration “upon request of the client” or “at the client’s sole discretion.” Some require that the architect agree to participate as a party in any arbitration involving the client and the contractor.

There are serious insurance implications. Under normal circumstances, the insurer is obliged to provide a defence

to the architect in the event the dispute qualifies as a Claim, as defined by the insurance policy. However, there is a

quid pro quo: The insurer has the right to manage the defence it is obliged to provide.

Tying the insurer’s hands through a contract provision prejudices the insurer’s ability to manage a key aspect of the

defence and is in neither the architect’s nor Pro-Demnity’s interests.

Additionally, policies may contain specific exclusions regarding agreements or actions taken by an insured architect –

measures that may imperil the insurer’s (i.e. Pro-Demnity’s) right of recovery of damages payable on behalf of the

architect from any other entity. They may also impose contractual liability upon the architect that would

not otherwise exist.

Why is this important?

At time of writing, Pro-Demnity is dealing with several Claims for which our ability to defend the architect has been significantly disadvantaged. In these cases, architects have accepted a contract provision binding them to participate in arbitration at the sole determination of the client.

As a further detriment, these provisions invariably increase the costs that Pro-Demnity must pay to defend the architect – additional costs that are borne by all of the architects participating in the program.

There are no inherent cost savings with the arbitration process when compared with processes reliant on the courts. Experience suggests the opposite: The costs may be substantially more, since the parties to the arbitration will need to pay for a venue as well as the arbitrator’s (or arbitrators’) fees.

Some client-authored dispute resolution provisions refer to protocols that require a panel of arbitrators – dramatically increasing the costs the architect will have agreed to share or assume.

Arbitration in Ontario, generally, has other significant drawbacks, including the inability to bring other parties into the

arbitration without their express consent.

When consent is not forthcoming from an entity that should be included, the parties to the arbitration may find themselves facing multiple actions with significant cost and litigation risk implications. Fortunately, this reality

sometimes encourages a client plaintiff to reconsider the wisdom of the contract provision. But this is too often not

the case.

Without these client-authored provisions in the contract, the decision to participate in an arbitration would involve mutual agreement of the parties to the dispute, in accordance with the rules in place in each jurisdiction.

Where the dispute qualified as a Claim, as defined by the architect’s professional liability policy, the decision to participate (or not), and in what capacity, would be based on the architect’s best interests.

Arbitration has its place, but it is not a panacea. In some instances it may be useful in resolving some aspect of a Claim.

However, it doesn’t make sense to attempt to determine the most appropriate and effective means of resolving a dispute or Claim until the issue arises, and the circumstances are understood.

What can an architect do?

Architects can help themselves and protect their insurance coverage by not agreeing to any binding dispute resolution provisions in a contract with a client or with a subconsultant. There is no need for these

provisions. As a practical matter, the parties to a dispute will always have the option to attempt resolution of any

dispute or disagreement by negotiation and mediation.

Mediation is simply negotiation using a facilitator. It has proven to be the most effective tool for resolving disputes that qualify as a Claim covered by professional liability insurance. Architects can insist upon no amendments to the wordings of the standard forms of agreement provided by the profession.

To address any perceived void, Pro-Demnity

has provided the OAA with a proposed

“Dispute Resolution” provision for

incorporation in the next planned update

to Document 600. The Pro-Demnity

proposal provides for the use of arbitration

“by mutual consent,” addressing

Pro-Demnity’s major concerns. Another

benefit will be the provision of an example

of appropriate dispute resolution wording

as a benchmark against which an architect

may compare any client-authored provisions.

Five things a Pro-Demnity lawyer doesn’t want to hear

John Little, Partner, Keel Cotrelle LLP

Over the years, I have had a great many initial meetings with architects and Pro-Demnity Claims Managers as we start to learn more about the Claim being made against the architect. During those years, I have developed a list of the

things I realize I don’t want to hear. These are five of the most important:

1. “We just had a verbal agreement”

It is surprising how many times even sophisticated architectural firms carrying out substantial projects have not entered into written agreements for their services, or are relying on a brief exchange of correspondence for their contract. Frequently, they will say, ” Well I had worked with that client for years,” or “We were in a rush,” or “I didn’t notice that our proposal wasn’t signed back.”

A written and signed contract (preferably OAA Document 600-2013) saves a lot of trouble down the road. It avoids any

arguments as to what the architect’s scope was to be, who was responsible for hiring other consultants and what the nature of the architect’s contract administration obligations were. It is so much easier once a dispute arises and the client says, “I thought the architect was going to ensure my building was put up properly,” to point to the provisions in the written agreement setting out clearly that the architect was not required to make continuous onsite reviews and was not to be responsible for errors or omissions of the contractor in failing to carry out the work in accordance

with the contract documents.

Equally important, OAA Document 600-2013 limits any Claim to the insurance available to the architect at the time the Claim is made. That is important protection for the architect. Often at the end of the project, the dispute is about money. A clearly written agreement will set out how the architect’s fee is to be calculated. Resolving that dispute by

reference to the agreement will frequently avoid massive counterclaims when a small Claim for fees outstanding is owing.

Remember, just sending the agreement signed by you to the client is not enough. Make sure the client signs the contract and returns it to you.

2. “I signed the agreement the owner sent me”

The only thing worse than having no written agreement is signing somebody else’s form of agreement without proper review.

The owner is your friend until there is a problem. The owner’s form of contract was not prepared to assist the architect

and it needs to be reviewed carefully, preferably with your lawyer.

A clause in an owner prepared agreement provided:

The architect agrees to indemnify and save harmless the client with respect to any damages suffered as a result of any failure to construct the building in accordance with the provisions of the plans and specifications and any applicable building codes.

This of course imposes onerous obligations on you, as the architect, which you cannot fulfill. You are not the contractor, you are not on site 24/7, and you cannot see everything in your periodic reviews. In addition, your

liability policy with Pro-Demnity excludes damages for any undertaking to indemnify where such provision

creates a liability in excess of that which might otherwise arise under law – as this wording certainly does.

A contract provision from a government institution provided:

In addition to the services set out above, the architect will supervise the execution and construction of the Work to the extent necessary and ensure that the construction is completed in accordance with the final designs, final architectural and engineering plans and specifications.

This is problematic in so many ways as it requires the architect to supervise construction, and in essence provide a guarantee of construction. Again you are not the contractor and there is no coverage for such a guarantee.

These are examples of owner’s contracts.

The same problem can arise with respect to your subconsultants’ agreements. Frequently, they may contain unreasonable limits on liability or indemnities on the part of the architect in favour of the subconsultants, leaving the architect to fill a financial gap between its liability to the owner and its right to collect from the subconsultants. They must be avoided. Use of document OAA 900 is encouraged when retaining subconsultants. Remember, if your arrangement with your subconsultant prejudices Pro-Demnity’s ability to defend you, it could lead to a denial of insurance coverage.

3. “I told my client I had made big mistake”

All architects want to help their clients and get the project completed. Mistakes do happen; however, that does not mean that the architect is negligent. That may or may not be true, but you are not the judge. If you feel you have made a significant error, the first thing to do is to advise Pro-Demnity. You do not need to have been sued, or to have received a threatening letter from your client. Rather, this obligation arises as soon as you might reasonably determine that circumstances exist which could subsequently give rise to a Claim against you. Failure to advise Pro-Demnity immediately could result in a denial of coverage.

There are many reasons for this. The first is that we all lose perspective and our judgment suffers when we think we have made a mistake. It is far better to have a dispassionate professional review the situation. You will know the old adage about the lawyer acting for themself having a fool for a client. This holds true for architects as well. In addition, while admitting to your client that you made an error may be good for your conscience, it may potentially void your insurance coverage, which specifically prohibits your admitting to an error.

4. “I lost/destroyed/never had records for the project”

Most disputes arise sometime after the completion of the project, even years later. In litigation, lawyers like to ask, “Do you remember what happened in the July 15, 2016 meeting?” or “Why do you say the plaintiff authorized that change?” That is where records (now mainly electronic) come into play.

As the project progresses, a mass of drawings and sketches will be prepared. The architect’s usual temptation may be to simply keep updating drawings and on occasion deleting the early drawings. The early drawings should be saved – particularly those that have been forwarded to the client for review. This is particularly important in fee disputes, for example, where there may be an issue as to whether the architect actually reviewed the drawings with the client, or whether they were even created.

The more work which is producible, the more likely it is the fee will be recovered. It is very important to confirm significant instructions in writing. A short email is fine. When a dispute arises, a written confirmation will be the best evidence that instructions were actually given. For example, “Dear Client, this will confirm your decision to use XYZ

cladding notwithstanding its higher long term maintenance cost.” It is important to prepare complete site visit reports. Architectural firms’ site visit reports vary dramatically. Some contain no information other than “The project appears to be proceeding satisfactorily.”

The Pro-Demnity Claims Manager in one meeting queried an architect as to why his site visit report contained so little information. The response was, “I thought it was better not to list anything so I could deny knowledge of any problems.” That of course is not particularly helpful when you are faced with multi-million dollar litigation. Reasonably detailed site visit reports show that you were conducting a proper review even if the particular item, which is ultimately at issue, is not referred to. The test is not whether you actually saw and identified the problem. The test is: Did you act in the manner that a reasonably competent architect would?

5. “Yes, that is my signature on the certificate”

The owner needs financing. The owner’s lawyer sends you a certificate and says I need it signed today before the project shuts down. I’ll be paying your outstanding fees out of the draw. The form says: Construction and development of the Project up to and including the Inspection Date has been performed in a good workmanlike manner and in accordance with the plans and specifications and all applicable building codes. This Certificate is given in connection with the above referenced advance under your construction letter agreement with the lender, and you may rely upon it in making such advance. You sign the form and email it back.

Three years later the project is in shambles. The lender cannot collect from the owner and pursues you on the basis of the Certificate. On discovery, the lawyer for the lender asks you, “Is that your signature? Was what you certified true?”

In another scenario, the project is complete and the local municipality will not give your client an occupancy permit without a final sign-off letter from you. The owner says every day is costing money. The form that you are being asked to sign says that you have inspected the construction and that it complies with your drawings and the Ontario Building Code. It omits the words “based on periodic site reviews” and omits the phrase “the construction is in general conformance with your drawings and the Ontario Building Code.”

Once again you are in a ZOOM discovery with the document being shared with you on the screen by plaintiff ’s counsel, and the question is asked, “is that your signature?” Although they often consist of only one page, certificates of final inspection are very important. Consider them carefully and if the wording is unusual, review it with your lawyer or Pro-Demnity before signing.

These are my top five. I hope not to hear them from you if/when we meet.

Our Contributor

John Little is a partner with Keel Cottrelle LLP, where he specializes in Civil Litigation and Insurance Law. Called to the Ontario Bar in 1976, he is a member of the Canadian and Ontario Bar Associations and the Advocates Society. John has been acting for Pro-Demnity Insurance Company since 1991, defending and providing advice to architects, while dealing primarily with professional negligence and professional discipline matters. When not spending quality time with architects or his golden retriever, John enjoys fishing and travel. John can be reached at: jlittle@keelcottrelle.ca

COSTS IN ADDITION

There are no nasty surprises – in this package, the batteries are included.

After reading our description of the Retirement from Practice Program, an architect asked us what the insurance term

“Costs in Addition” means. It appears to be saying that Pro-Demnity’s obligation doesn’t cover the defence – that the retired architect is solely responsible for paying any legal and defence costs.

The opposite is true. “Costs in Addition” means that the costs to the insurer are paid by the insurer (Pro-Demnity in this case), and not by the insured (the architect), and they are in addition to the Claim limits that apply to any damages that the insurer pays. This is good news.

On the other hand, if a policy were to say “Costs Included” or “Inclusive of Costs,” it means that any defence costs incurred by the insurer in the defence of an architect are included in the Claim limits. As a result, any costs that the insurer pays to defend the architect are taken from the funds available for the payment of damages. In extreme cases, these costs can erode the entire Claim limit, leaving nothing for damages awarded against the architect.

“Costs in Addition” is a benefit to the architect; “Costs Included” is not.

The Straight Line is a newsletter for architects and others interested in the profession. It is published by Pro-Demnity Insurance Company to provide a forum for discussion of a broad range of issues affecting architects and their professional liability insurance.